Afrikaans

| Afrikaans | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [ɐfriˈkɑːns] | |

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Southern Africa | |

| Total speakers | over 6 million (native) between 15–23 million (total)[n 1] |

|

| Ranking | 99 | |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | ||

| Regulated by | Die Taalkommissie | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | af | |

| ISO 639-2 | afr | |

| ISO 639-3 | afr | |

| Linguasphere | ||

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Afrikaans is a West Germanic language, mainly spoken in South Africa and Namibia. It is a daughter language of Dutch, originating in its 17th century dialects, collectively referred to as Cape Dutch.[n 2] Although Afrikaans borrowed from languages such as Malay, Portuguese, the Bantu languages or the Khoisan languages, an estimated 90 to 95 percent of Afrikaans vocabulary is ultimately of Dutch origin.[n 3] Therefore, differences with Dutch often lie in a more regular morphology, grammar, and spelling of Afrikaans.[n 4] There is a degree of mutual intelligibility between the two languages—especially in written form—although it is easier for Dutch-speakers to understand Afrikaans than the other way round.[n 5]

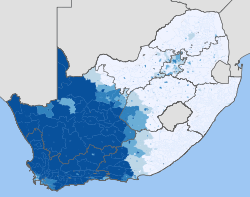

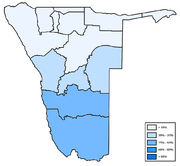

With about 6 million native speakers in South Africa, or 13.3 percent of the population, it is the third most spoken mother tongue in the country.[1][2] It has the widest geographical and racial distribution of all official languages, and is widely spoken and understood as a second or third language.[n 6] It is the majority language of the western half of South Africa—the provinces of the Northern Cape and Western Cape—and the primary language of the coloured and white communities.[n 7] In neighbouring Namibia, Afrikaans is spoken in 11 percent of households, mainly concentrated in the capital Windhoek and the southern regions of Hardap and Karas.[n 8] Widely spoken as a second language, it is a lingua franca of Namibia.[n 9]

While the number of total speakers of Afrikaans is unknown, estimates range between 15 and 23 million.[n 1]

Contents |

Vowel sounds[3]

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lab. | |||

| Close | i | yː | u | |

| Mid | ɛ, ɛː | œ | ə | ɔ, ɔː |

| Open | ɐ | ɑː | ||

Orthography

There are many parallels to the Dutch orthography conventions and those used for Afrikaans. There are 26 letters.

In Afrikaans, many consonants are dropped from the earlier Dutch spelling. For example, slechts ('only') in Dutch becomes slegs in Afrikaans. Part of this is because the spelling of Afrikaans words is considerably more phonemic than that of Dutch. For example, Afrikaans and some Dutch dialects make no distinction between /s/ and /z/, having merged the latter into the former; while the word for "south" is written ‹zuid› in Dutch, it is spelled ‹suid› in Afrikaans to represent this merger. Similarly, the Dutch digraph‹ij› is written as ‹y›, except where it replaces the Dutch suffix –lijk, as in waarschijnlijk > waarskynlik.

Another difference is the indefinite article, 'n in Afrikaans and een in Dutch. 'A book' is 'n boek in Afrikaans, whereas it is either een boek or 'n boek in Dutch. This 'n is usually pronounced as just a weak vowel, [ə].

The diminutive suffix in Afrikaans is ‹-jie›, whereas in Dutch it is ‹-je›, hence "a little bit" is bietjie in Afrikaans and beetje in Dutch.

The letters ‹c›, ‹q›, ‹x›, and ‹z› occur almost exclusively in borrowings from French, English, Greek and Latin. This is usually because words that had ‹c› and ‹ch› in the original Dutch are spelled with ‹k› and ‹g›, respectively, in Afrikaans. Similarly original ‹qu› and ‹x› are spelt ‹kw› and ‹ks› respectively. For example ‹ekwatoriaal› instead of ‹equatoriaal›, and ‹ekskuus› instead of ‹excuus›.

The vowels with diacritics in non-loanword Afrikaans are: ‹á, é, è, ê, ë, í, î, ï, ó, ô, ú, û, ý›. Diacritics are ignored when alphabetising, though they are still important, even when typing the diacritic forms may be difficult.

Initial apostrophes

A few short words in Afrikaans take initial apostrophes. In modern Afrikaans, these words are always written in lower case (except if the entire line is uppercase), and if they occur at the beginning of a sentence, the next word is capitalised. Three examples of such apostrophed words are 'k, 't, 'n. The last (the indefinite article) is the only apostrophed word that is common in written Afrikaans, since the other examples are shortened versions of other words (ek and het respectively).[4]

Here are a few examples:

| Apostrophed Version | Usual Version | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'n Man loop daar | (none) | A man walks there | |

| 'k 't Dit gesê | Ek het dit gesê | I said it | Extremely uncommon |

| 't Jy dit geëet? | Het jy dit geëet? | Did you eat it? | Extremely uncommon |

The apostrophe and the following letter are regarded as two separate characters, and are never written using a single glyph, although a single character variant of the indefinite article appears in Unicode, ʼn.

Table of characters

For more on the pronunciation of the below letters, see Wikipedia:IPA for Dutch and Afrikaans.

| Grapheme | IPA | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| a | /ɐ/ | appel ('apple') |

| aa | /ɑː/ | aap ('monkey') |

| aai | /ɑːi/ | draai ('turn') |

| ai | /aj/ | baie ('many') |

| b | /b/ | boom ('tree') |

| c | /s/, /k/ | (found only in borrowed words; the former pronunciation occurs before 'e', 'i', or 'y') |

| ch | /ʃ/, /x/, /k/ | chirurg ('surgeon'; /ʃ/, typically 'sj' is used instead), chemie ('chemistry'; /x/), chitien ('chitin'; /k/). Found only in loanwords and proper names |

| d | /d/ | dae ('days') |

| dj | /d͡ʒ/ | djati ('teak') (used to transcribe foreign words) |

| e | /ɛ/, /iˑe/, /ə/ | se (indicates possessive, for example 'Jan se boom', meaning 'John's tree') |

| ê | /ɛː/ | sê ('say' or 'says') |

| ë | /i/ | oë ('eyes') |

| ee | /eə/ | weet ('know' or 'knows') |

| eeu | /iu/ | sneeu ('snow') |

| ei | /ɛi/ | Mei ('May") |

| eu | /eø/ | seun ('boy') |

| f | /f/ | fiets ('bicycle') |

| g | /x/ | goed ('good') |

| gh | /ɡ/ | gholf ('golf'). Used for /ɡ/ when it is not an allophone of /x/; found only in borrowed words |

| h | /ɦ/ | hael ('hail') |

| i | /i/ | kind ('child') |

| ie | /i/ | iets ('something') |

| j | /j/ | jonk ('young') |

| k | /k/ | kat ('cat') |

| l | /l/ | lae ('layers') |

| m | /m/ | man ('man') |

| n | /n/ | nael ('nail') |

| ng | /ŋ/ | sing ('sing') |

| o | /ɔ/ | op ('on') |

| ô | /ɔː/ | môre ('tomorrow') |

| oe | /u/ | boek ('book') |

| oei | /ui/ | koeie ('cows') |

| oi | /oj/ | mooi ('pretty' or 'beautiful') - Sometimes spelled 'oy' in loanwords and surnames |

| oo | /oə/ | brood ('bread') |

| ooi | /ɔːi/ | nooi (saying for little girl) |

| ou | /ɵu/ | koud ('cold') |

| p | /p/ | pot ('pot') |

| q | /k/ | (found only in foreign words with original spelling maintained; typically ‹k› is used instead) |

| r | /r/ | rooi ('red') |

| s | /s/ | ses ('six') |

| sj | /ʃ/ | sjaal ('shawl') |

| t | /t/ | tafel ('table') |

| tj | /tʃ/, /k/ | tjank ('whine' or 'to cry incessantly'). (The former pronunciation occurs at the beginning of a word and the latter in ‹-tjie›) |

| u | /œ/ | kus ('coast') |

| û | /œː/ | brûe ('bridges') |

| ui | /œj/ | huis ('house') - sometimes spelled 'uy' in loanwords and surnames, e.g. Spuy |

| uu | /y/ | suutjies ('quietly') |

| v | /f/ | vis ('fish') |

| w | /v/ | water ('water') |

| x | /ks/ | xifoïed ('xiphoid') |

| y | /ɛi/ | byt ('bite') |

| z | /z/ | Zoeloe ('Zulu'). Found only in onomatopoeia and loanwords |

History

The Afrikaans language originated mainly from Dutch[5][6] and developed in South Africa. It is often said that Dutch and Afrikaans are mutually intelligible, however, this is often not true[7][8] as Afrikaans tends to have inherited a lot of its vocabulary and language characteristics from other languages such as Portuguese, Malay, Bantu languages and Khoisan languages[9][10], but despite this, it is still possible for a Dutch person to understand an Afrikaans person quite well. As well as this, Afrikaans is also grammatically far simpler than Dutch, and a large amount of unique slang words are present in Afrikaans, which are absent in Dutch. It was considered a Dutch dialect in South Africa up until the late 19th century when it became recognised as a distinct language.[11] A relative majority of the first settlers whose descendants today are the Afrikaners were from the United Provinces (now Netherlands), though there were also many from Germany, a considerable number from France, and some from Norway, Portugal, Scotland, and various other countries.

The workers and slaves who contributed to the development of Afrikaans were Asians (especially Malays), Malagasys, as well as the Khoi, Bushmen and Bantu peoples who also lived in the area. African creole people in the early 1700s — documented on the cases of Hendrik Bibault and patriarch Oude Ram — were the first to call themselves Afrikaner (Africans). This is where Afrikaans got its name from.[12] Only much later in the second half of the 19th century did the Boers adopt this attribution, too,[13] and referred to the Khoi-slave descendants as Coloureds.[12]

Dialects

Following early dialectical studies of Afrikaans, it was theorised that three main historical dialects probably existed after the Great Trek in the 1830s. These dialects are defined as the Northern Cape, Western Cape and Eastern Cape dialects. Remnants of these dialects still remain in present-day Afrikaans although the standardising effect of Standard Afrikaans has contributed to a great levelling of differences in modern times.

There is also a prison cant known as soebela, or sombela which is based on Afrikaans yet heavily influenced by Zulu. This language is used as a secret language in prison and is taught to initiates.[14]

Expatriate geolect

Although mainly spoken in South Africa and Namibia, smaller Afrikaans-speaking populations live in Australia, Botswana, Canada, Lesotho, Malawi, New Zealand, Swaziland, the United States, Zambia and Zimbabwe.[15] Most, if not all, Afrikaans speaking people living outside of Africa are emigrants who have left South Africa. Because of emigration and migrant labour, there are possibly over 100,000 Afrikaans speakers in the United Kingdom. The geolect of Afrikaans spoken outside South Africa in these predominantly English-speaking countries has been referred to as "soutmielie".[16][17][18][19]

Standardisation

The linguist Paul Roberge suggests that the earliest 'truly Afrikaans' texts are doggerel verse from 1795 and a dialogue transcribed by a Dutch traveller in 1825. Printed material among the Afrikaners at first used only standard European Dutch. By the mid-19th century, more and more were appearing in Afrikaans, which was very much still regarded as a set of regional dialects.

In 1861, L.H. Meurant published his Zamenspraak tusschen Klaas Waarzegger en Jan Twyfelaar ("Conversation between Claus Truthsayer and John Doubter"), which is considered by some to be the first authoritative Afrikaans text. Abu Bakr Effendi also compiled his Arabic Afrikaans Islamic instruction book between 1862 and 1869, although this was only published and printed in 1877. The first Afrikaans grammars and dictionaries were published in 1875 by the Genootskap vir Regte Afrikaners ('Society for Real Afrikaners') in Cape Town.

The First and Second Boer Wars further strengthened the position of Afrikaans. The official languages of the Union of South Africa were English and Dutch until Afrikaans was subsumed under Dutch on 5 May 1925.

The main Afrikaans dictionary is the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) (Dictionary of the Afrikaans Language), which is as yet incomplete owing to the scale of the project, but the one-volume dictionary in household use is the Verklarende Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (HAT). The official orthography of Afrikaans is the Afrikaanse Woordelys en Spelreëls, compiled by Die Taalkommissie.

The Afrikaans Bible

A major landmark in the development of Afrikaans was the full translation of the Bible into the language. Prior to this most Cape Dutch-Afrikaans speakers had to rely on the Dutch Statenbijbel. The aforementioned Statenvertaling had its origins with the Synod of Dordrecht and was thus in an archaic form of Dutch. This rendered understanding difficult at best to Dutch and Cape Dutch speakers, moreover increasingly unintelligible to Afrikaans speakers.

C. P. Hoogehout, Arnoldus Pannevis, and Stephanus Jacobus du Toit were the first Afrikaans Bible translators. Important landmarks in the translation of the Scriptures were in 1878 with C. P. Hoogehout's translation of the Evangelie volgens Markus (Gospel of Mark), however this translation was never published. The manuscript is to be found in the South African National Library, Cape Town.

The first official Bible translation of the entire Bible into Afrikaans was in 1933 by J. D. du Toit, E. E. van Rooyen, J. D. Kestell, H. C. M. Fourie, and BB Keet.[20][21] This monumental work established Afrikaans as 'n suiwer en oordentlike taal, that is "a pure and proper language" for religious purposes, especially amongst the deeply Calvinist Afrikaans religious community that had hitherto been somewhat sceptical of a Bible translation out of the original Dutch language to which they were accustomed.

In 1983 there was a fresh translation in order to mark the 50th anniversary of the original 1933 translation and provide much needed revision. The final editing of this edition was done by E. P. Groenewald, A. H. van Zyl, P. A. Verhoef, J. L. Helberg and W. Kempen.

Afrikaans Version of the Lord's Prayer. Onse Vader.[22]

Onse Vader wat in die hemele is, laat U naam geheilig word. Laat U koninkryk kom, laat U wil geskied, soos in die hemel net so ook op die aarde. Gee ons vandag ons daaglikse brood, en vergeef ons ons skulde, soos ons ook ons skuldenaars vergewe. En lei ons nie in versoeking nie, maar verlos ons van die bose. Want aan U behoort die Koninkryk en die krag en die heerlikheid, tot in ewigheid. Amen.

Grammar

In Afrikaans grammar, there is no distinction between the infinitive and present forms of verbs, with the exception of the verbs 'to be' and 'to have':

| infinitive form | present indicative form | Dutch | English | German |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wees | is | zijn | be | sein |

| hê | het | hebben | have | haben |

In addition, verbs do not conjugate differently depending on the subject. For example,

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English | German |

|---|---|---|---|

| ek is | ik ben | I am | ich bin |

| jy/u is | jij/U bent | you are (sing.) | du bist (informal sing.) |

| hy/sy/dit is | hij/zij/het is | he/she/it is | er/sie/es ist |

| ons is | wij zijn | we are | wir sind |

| julle is | jullie zijn | you are (plur.) | ihr seid (informal pl.) |

| hulle is | zij zijn | they are | Sie (formal sing. & pl.)/sie sind |

The preterite looks exactly like the present but is indicated by adverbs like toe, the exception being 'to be'.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English | German |

|---|---|---|---|

| ek was | ik was | I was | ich war |

The perfect tense is sometimes preferred over the preterite in literature where the preterite would be used in Dutch or English, for example, in the case of the verb to drink:

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English | German |

|---|---|---|---|

| ek het gedrink. | ik dronk. | I drank. | ich trank. |

In other respects, the perfect tense in Afrikaans follows Dutch and English.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English | German |

|---|---|---|---|

| ek het gedrink | ik heb gedronken. | I have drunk. | ich habe getrunken. |

Afrikaans phrases

Afrikaans is a very centralised language, meaning that most of the vowels are pronounced in a very centralised (i.e. very schwa-like) way. Although there are many different dialects and accents, the transcription should be fairly standard.

| Afrikaans | IPA | Dutch | English | German |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallo! Hoe gaan dit? | [ɦaləu ɦu xaˑn dət] | Hallo! Hoe gaat het (met je/jou/u)? Also used: Hallo! Hoe is het? |

Hello! How is it going (Hello! How are you?) | Hallo! Wie geht's? |

| Baie goed, dankie. | [bajə xuˑt danki] | Heel goed, dank je. | Very well, thank you. | Mir geht's gut, danke. |

| Praat jy Afrikaans? | [prɑˑt jəi afrikɑ̃ˑs] | Spreek/praat je Afrikaans? | Do you speak Afrikaans? | Sprichst du Afrikaans? |

| Praat jy Engels? | [prɑˑt jəi ɛŋəls] | Spreek/praat je Engels? | Do you speak English? | Sprichst du Englisch? |

| Ja. | [jɑˑ] | Ja. | Yes. | Ja. |

| Nee. | [neˑə] | Nee. | No. | Nein. |

| 'n Bietjie. | [ə biki] | Een beetje. | A bit. | Ein Bißchen. |

| Wat is jou naam? Less common: Hoe heet jy? |

[vat əs jəu nɑˑm] | Hoe heet je? Less common: Wat is jouw naam? |

What is your name? | Wie heißt du? Wie ist dein Name? |

| Die kinders praat Afrikaans. | [di kənərs prɑˑt afrikɑˑns] | De kinderen praten Afrikaans. | The children speak Afrikaans. | Die Kinder sprechen Afrikaans. |

| Ek is lief vir jou. Less common: Ek het jou lief. |

[æk əs lif fir jœʉ] | Ik hou van je/jou. Less common: Ik heb je/jou lief. |

I love you. | Ich liebe dich. Also: Ich habe dich lieb. |

Note: The word Afrikaans means African (in the general sense) in the Dutch language. Although considered incorrect, the word Zuid-Afrikaans, lit. "South African", is sometimes used to avoid confusion when referring specifically to the Afrikaans language. This problem also occurs in Afrikaans itself, resolved by using the words Afrika and Afrikaan to distinguish from Afrikaans(e) and Afrikaner respectively.

A sentence having the same meaning and written identically in Afrikaans and English is:

- My pen was in my hand. ([məi pɛn vas ən məi hɑnt])

Similarly the sentence:

- My hand is in warm water. ([məi hɑnt əs ən varəm vɑˑtər])

has almost identical meaning in Afrikaans and English although the Afrikaans warm corresponds more closely in meaning to English hot.

Sample text in Afrikaans

Psalm 23. 1983 Translation:

- Die Here is my Herder, ek kom niks kort nie.

- Hy laat my in groen weivelde rus. Hy bring my by waters waar daar vrede is.

- Hy gee my nuwe krag. Hy lei my op die regte paaie tot eer van Sy naam.

- Selfs al gaan ek deur donker dieptes, sal ek nie bang wees nie, want U is by my. In U hande is ek veilig.

Translation Dependant:

- Die Here is my Herder, niks sal my ontbreek nie.

- Hy laat my neerlê in groen weivelde; na waters waar rus is, lei Hy my heen.

- Hy verkwik my siel; Hy lei my in die spore van geregtigheid, om sy Naam ontwil.

- Al gaan ek ook in 'n dal van doodskaduwee, ek sal geen onheil vrees nie; want U is met my: u stok en u staf die vertroos my.

- U berei die tafel voor my aangesig teenoor my teëstanders; U maak my hoof vet met olie; my beker loop oor.

- Net goedheid en guns sal my volg al die dae van my lewe; en ek sal in die huis van die HERE bly in lengte van dae.

- The Lord is my shepherd I shall not be in want.

- He makes me lie down in green pastures, he leads me beside quiet waters.

- He restores my soul. He guides me in paths of righteousness for his name's sake.

- Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil for you are with me; your rod and staff they comfort me.

| Lord's prayer (Afrikaans New Living translation) |

|---|

| Ons Vader in die hemel, laat U Naam geheilig word.

Laat U koningsheerskappy spoedig kom. Laat U wil hier op aarde uitgevoer word soos in die hemel. Gee ons die porsie brood wat ons vir vandag nodig het. En vergeef ons ons sondeskuld soos ons ook óns skuldenaars vergewe het. Bewaar ons sodat ons nie aan verleiding sal toegee nie; en bevry ons van die greep van die Bose. Want van U is die koninkryk, en die krag, en die heerlikheid, tot in ewigheid. Amen |

Original (Suiwer Afrikaans) Onse Vader:

Onse Vader wat in die hemel is, laat U Naam geheilig word; laat U koninkryk kom; laat U wil geskied op die aarde, net soos in die hemel. Gee ons vandag ons daaglikse brood; en vergeef ons ons skulde soos ons ons skuldenaars vergewe en laat ons nie in die versoeking nie maar verlos ons van die Bose Want aan U behoort die koninkryk en die krag en die heerlikheid tot in ewigheid. Amen

Sociolinguistics

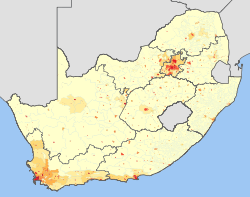

| 0–20% 20–40% 40–60% | 60–80% 80–100% No population |

| <1 /km² 1–3 /km² 3–10 /km² 10–30 /km² 30–100 /km² | 100–300 /km² 300–1000 /km² 1000–3000 /km² >3000 /km² |

Afrikaans is the first language of over 80% of Coloured South Africans (3.1 million people) and approximately 60% of White South Africans (2.5 million). Around 200,000 black South Africans speak it as their first language.[23] Large numbers of Bantu-speaking and English-speaking South Africans also speak it as their second language.

Some state that the term Afrikaanses should be used as a term for all people who speak Afrikaans, without respect to ethnic origin, instead of "Afrikaners", which refers to an ethnic group, or "Afrikaanssprekendes" (lit. people that speak Afrikaans). Linguistic identity has not yet established that one term be favoured above another and all three are used in common parlance.[24]

It is also widely spoken in Namibia, where it has had constitutional recognition as a national, but not official, language since independence in 1990. Prior to independence, Afrikaans had equal status with German as an official language. There is a much smaller number of Afrikaans speakers among Zimbabwe's white minority, as most have left the country since 1980. Afrikaans was also a medium of instruction for schools in Bophuthatswana Bantustan.[25]

Many South Africans living and working in Belgium, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Kuwait and the United Kingdom are also Afrikaans-speaking. There are Afrikaans websites, among them, news sites such as http://www.nuus24.com, and radio broadcasts over the web, such as those from Radio Sonder Grense and Radio Pretoria.

Afrikaans has been influential in the development of South African English. Many Afrikaans loanwords have found their way into South African English, such as 'bakkie' ("pickup truck"), 'braai' ("barbecue"), 'tekkies' ("sneakers"). A few words in standard English are derived from Afrikaans, such as 'aardvark' (lit. "earth pig"), 'trek' ("pioneering journey", in Afrikaans lit. "pull" but used also for "migrate"), "spoor" ("animal track"), "veld" ("Southern African grassland" in Afrikaans lit. "field"), "commando" from Afrikaans "kommando" meaning small fighting unit, "boomslang" ("tree snake") and apartheid ("segregation"; more accurately "apartness" or "the state or condition of being apart").

In 1976, high school students in Soweto began a rebellion in response to the government's decision that Afrikaans be used as the language of instruction for half the subjects taught in non-White schools (with English continuing for the other half). Although English is the mother tongue of only 8.2% of the population, it is the language most widely understood, and the second language of a majority of South Africans.[26] Afrikaans is more widely spoken than English in the Northern and Western Cape provinces, several hundred kilometers from Soweto. The Black community's opposition to Afrikaans and preference for continuing English instruction was underscored when the government rescinded the policy one month after the uprising: 96% of Black schools chose English (over Afrikaans or native languages) as the language of instruction.[27]

Under South Africa's Constitution of 1996, Afrikaans remains an official language, and has equal status to English and nine other languages. The new policy means that the use of Afrikaans is now, in effect, often reduced in favour of English, or to accommodate the other official languages. In 1996, for example, the South African Broadcasting Corporation reduced the amount of television airtime in Afrikaans, while South African Airways dropped its Afrikaans name Suid-Afrikaanse Lugdiens from its livery. Similarly, South Africa's diplomatic missions overseas now only display the name of the country in English and their host country's language, and not in Afrikaans.

In spite of these moves, the language has remained strong, and Afrikaans newspapers and magazines continue to have large circulation figures. Indeed, the Afrikaans-language general-interest family magazine Huisgenoot has the largest readership of any magazine in the country. In addition, a pay-TV channel in Afrikaans called KykNet was launched in 1999, and an Afrikaans music channel, MK, in 2005. A large number of Afrikaans books are still published every year, mainly by the publishers Human & Rousseau, Tafelberg Uitgewers, Struik, and Protea Boekhuis.

Afrikaans has two monuments erected in its honour. The first was erected in Burgersdorp, South Africa, in 1893, and the second, better-known Afrikaans Language Monument (Afrikaanse Taalmonument) was built in Paarl, South Africa, in 1975.

When the British design magazine Wallpaper described Afrikaans as "one of the world's ugliest languages" in its September 2005 article about the Monument, South African billionaire Johann Rupert (chairman of the Richemont group), responded by withdrawing advertising for brands such as Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Montblanc and Alfred Dunhill from the magazine.[28] The author of the article, Bronwyn Davies, was an English-speaking South African.

Modern Dutch and Afrikaans share 85-plus per cent of their vocabulary. Afrikaans speakers are able to learn Dutch within a comparatively short time. Native Dutch speakers pick up written Afrikaans even more quickly, due to its simplified grammar, whereas understanding spoken Afrikaans might need more effort. Afrikaans speakers can learn Dutch pronunciation with little training. This has enabled Dutch and Belgian companies to outsource their call centre operations to South Africa.[29]

Future of Afrikaans

Post-apartheid South Africa has seen a loss of preferential treatment by the government for Afrikaans, in terms of education, social events, media (TV and Radio), and general status throughout the country, given that it now shares its place as official language with ten other languages. Nevertheless, Afrikaans remains more prevalent in the media - radio, newspapers and television[30] - than all the other official languages, except for English. More than 300 titles in Afrikaans are published per year.[31]

Through all the problems of depreciation and migration that Afrikaans faces today, the language still competes well, with Afrikaans DSTV channels (pay channels) and high newspaper and CD sales as well as popular internet sites. A resurgence in Afrikaans popular music (from the late 1990s) has added new momentum to the language especially among the younger generations in South Africa. The latest contribution to building the Afrikaans language is the availability of pre-school educational CDs and DVDs. These are also popular with large Afrikaans-speaking expatriate communities seeking to retain the language in family context. After years of inactivity, the Afrikaans language cinema is also starting to reactivate. With the 2007 film Ouma se slim kind, the first full length Afrikaans movie since Paljas from 1998, a new era for Afrikaans cinema started. Several short-films have been created and more feature-length movies such as Poena is Koning and Bakgat, both from 2008 have been produced.

Afrikaans also seems to be returning to the SABC. SABC3 stated in the beginning of 2009 that it will increase Afrikaans programming because of the needs of the "growing Afrikaans-language market and their need for working capital as Afrikaans advertising is the only advertising that sells in the current South African TV market". In April 2009, SABC3 started showing several Afrikaans-language programmes.[32]

Further latent support for the language is the de-politicised view of younger-generation South Africans: it is less and less viewed as "the language of the oppressor" and this is supported to a large extent by new-generation Afrikaans youths openly supporting a reformation of old Afrikaner nationalist racial policy.

See also

- Aardklop Arts Festival

- Arabic Afrikaans

- Languages of South Africa

- List of Afrikaans language poets

- List of English words of Afrikaans origin

- Afrikaans speaking population in South Africa

- South African Translators' Institute

- Differences between Afrikaans and Dutch

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 What follows are estimations. Afrikaans has 16.3 million speakers; see de Swaan 2001, p. 216. Afrikaans has a total of 16 million speakers; see Machan 2009, p. 174. About 9 million people speak Afrikaans as a second or third language; see Alant 2004, p. 45, Proost 2006, p. 402. Afrikaans has over 5 million native speakers and 15 million second language speakers; see Réguer 2004, p. 20. Afrikaans has about 6 million native and 16 million second language speakers; see Domínguez & López 1995, p. 340. In South Africa, over 23 million people speak Afrikaans, of which a third are first-language speakers; see Page & Sonnenburg 2003, p. 7. L2 "Black Afrikaans" is spoken, with different degrees of fluency, by an estimated 15 million; see Stell 2008-11, p. 1.

- ↑ Afrikaans is a daughter language of Dutch; see Booij 1995, p. 2, Jansen, Schreuder & Neijt 2007, p. 5, Mennen, Levelt & Gerrits 2006, p. 1, Booij 2003, p. 4, Hiskens, Auer & Kerswill 2005, p. 19, Heeringa & de Wet 2007, p. 1, 3, 5.

Afrikaans was historically called Cape Dutch; see Deumert & Vandenbussche 2003, p. 16, Conradie 2005, p. 208, Sebba 1997, p. 160, Langer & Davies 2005, p. 144, Deumert 2002, p. 3, Berdichevsky 2004, p. 130.

Afrikaans is rooted in seventeenth century dialects of Dutch; see Holm 1989, p. 338, Geerts & Clyne 1992, p. 71, Mesthrie 1995, p. 214, Niesler, Louw & Roux 2005, p. 459.

Afrikaans is variously described as a creole, a partially creolised language, or a deviant variety of Dutch; see Sebba 2007, p. 116. - ↑ Afrikaans borrowed from other languages such as Portuguese, Malay, Bantu and Khoisan languages; see Sebba 1997, p. 160, Niesler, Louw & Roux 2005, p. 459.

90 to 95 percent of Afrikaans vocabulary is ultimately of Dutch origin; see Mesthrie 1995, p. 214, Mesthrie 2002, p. 205, Kamwangamalu 2004, p. 203, Berdichevsky 2004, p. 131, Brachin & Vincent 1985, p. 132 - ↑ For morphology; see Holm 1989, p. 338, Geerts & Clyne 1992, p. 72. For grammar and spelling; see Sebba 1997, p. 161.

- ↑ Dutch and Afrikaans share mutual intelligibility; see Gooskens 2007, p. 453, Holm 1989, p. 338, Baker & Prys Jones 1997, p. 302, Egil Breivik & Håkon Jahr 1987, p. 232.

For written mutual intelligibility; see Sebba 2007, p. 116, Sebba 1997, p. 161.

It is easier for Dutch-speakers to understand Afrikaans than the other way around; see Gooskens 2007, p. 454. - ↑ It has the widest geographical and racial distribution of all official languages; see Webb 2003, p. 7, 8, Berdichevsky 2004, p. 131. It has by far the largest geographical distribution; see Alant 2004, p. 45.

It is widely spoken and understood as a second or third language; see Deumert & Vandenbussche 2003, p. 16, Kamwangamalu 2004, p. 207, Myers-Scotton 2006, p. 389, Simpson 2008, p. 324, Palmer 2001, p. 141, Webb 2002, p. 74, Herriman & Burnaby 1996, p. 18, Page & Sonnenburg 2003, p. 7, Brook Napier 2007, p. 69, 71.

An estimated 40 percent have at least a basic level of communication; see Webb 2003, p. 7 McLean & McCormick 1996, p. 333. - ↑ According to the 2001 census, 79.5% of the so-called coloured community used Afrikaans as home language, 59.1% of the white population, 1.7% of the Indian population and 0.7% of the black population.

For the geographical distribution of Afrikaans; see also Afrikaans speaking population in South Africa. - ↑ Afrikaans is spoken in 11 percent of Namibian households; see Namibian Population Census 2001. In the Hardap Region it is spoken in 44 percent of households, in the Karas Region by 40 percent of households, in the Khomas Region by 24 percent of households; see Census Indicators, 2001 and click through to "Regional indicators".

- ↑ Some 85 percent of Namibians can understand Afrikaans; see Bromber & Smieja 2004, p. 73.

There are 152,000 native speakers of Afrikaans in Namibia; see Deumert & Vandenbussche 2003, p. 16.

Afrikaans is a lingua franca of Namibia; see Deumert 2004, p. 1, Adegbija 1994, p. 26, Batibo 2005, p. 79, Donaldson 1993, p. xiii, Deumert & Vandenbussche 2003, p. 16, Baker & Prys Jones 1997, p. 364, Domínguez & López 1995, p. 399, Page & Sonnenburg 2003, p. 8, CIA 2010.

References

- ↑ "Census 2001 - Home language". Statistics South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za/PublicationsHTML/Report-03-02-042001/html/Report-03-02-042001_18.html?gInitialPosX=10px&gInitialPosY=10px&gZoomValue=100. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ↑ "Census 2001: Primary tables South Africa: Census 1996 and 2001 compared". Statistics South Africa. Statistics South Africa. 2001. p. 19. http://www.statssa.gov.za/census01/html/RSAPrimary.pdf.

- ↑ Lass (1984:93)

- ↑ http://www.101languages.net/afrikaans/grammar.html Retrieved 12 April 2010

- ↑ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/afrikaans.htm Retrieved 12 April 2010

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/8437/Afrikaans-language Retrieved 12 April 2010

- ↑ Gooskens, Charlotte (2007). The Contribution of Linguistic Factors to the Intelligibility of Closely Related Languages. Routledge. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a907115517&db=all. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/language/about/afrikaans.html Retrieved 12 April 2010

- ↑ http://www.worldlanguage.com/languages/afrikaans.htm Retrieved 3 April 2010

- ↑ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/afrikaans.htm Retrieved 3 April 2010

- ↑ http://www.keylanguages.com/new_english/afrikaans.html Retrieved 12 April 2010

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Slavery in the Cape". Institute for the Study of Slavery and its Legacy – South Africa. http://slaveryinstitute.wordpress.com/slavery-in-the-cape/. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "The Orlams Afrikaners - the Creole Africans of the Garieb". Cape Slavery Heritage. http://cape-slavery-heritage.iblog.co.za/category/new-creole-identities/page/4/. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Afrikaans 101 http://www.101languages.net/afrikaans/history.html Retrieved 24 April 2010

- ↑ Lewis (2009)

- ↑ "vetweet - Chilapalapa". Litnetblogs.24.com. 2009-01-12. http://litnetblogs.24.com/ViewComments.aspx?blogid=e5d4e396-82b5-4eba-86f7-789914dc866b&mid=9410586a-31e6-46c1-9715-86e32bf75a54. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "Major League Baseball". Forums.mlb.com. http://www.forums.mlb.com/n/pfx/forum.aspx?tsn=194&nav=messages&webtag=ml-mlb&tid=80777. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "Afrikaanse Taalmuseum open in Pretoria". LitNet. 2008-09-24. http://www.litnet.co.za/cgi-bin/giga.cgi?cmd=cause_dir_news_item&news_id=53260&cause_id=1270. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ The term comes from sout ('salt') and mielie ('corn'), likely in reference to soutpiel, derogatory term for white English-speaking South Africans. The metaphor is that such a person has one foot in England and one foot in South Africa, with his "corn" or penis hanging in the sea.

- ↑ Bogaards, Attie H.. "Bybelstudies" (in af). http://www.enigstetroos.org/bybelstudie.htm. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ "Afrikaanse Bybel vier 75 jaar" (in af). Bybelgenootskap van Suid-Afrika. 2008-08-25. http://www.bybelgenootskap.co.za/afr/bybelgenootskap/jongste_nuus.asp. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Onse Vader : Afrikaans.

- ↑ "South African Census" (PDF). http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/CinBrief/CinBrief2001.pdf. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ Die dilemma van ‘n gedeelde Afrikaanse identiteit: Kan wit en bruin mekaar vind?.

- ↑ "Armoria patriæ - Republic of Bophuthatswana". Archived from the original on 2009-10-25. http://www.webcitation.org/5kmVdolSf.

- ↑ Govt info available online in all official languages - South Africa - The Good News.

- ↑ Black Linguistics: Language, Society and Politics in Africa and the Americas, by Sinfree Makoni, p. 120S.

- ↑ Afrikaans stars join row over 'ugly language' Cape Argus, December 10, 2005.

- ↑ "SA holds its own in global call centre industry", eProp Commercial Property News in South Africa.

- ↑ Oranje FM, Radio Sonder Grense, Jacaranda FM, Radio Pretoria, Rapport, Beeld, Die Burger, Die Son, Afrikaans news is run everyday; the PRAAG website is a web-based news service. On pay channels it is provided as second language on all sports, Kyknet

- ↑ "Hannes van Zyl". Oulitnet.co.za. http://www.oulitnet.co.za/taaldebat/multilin.asp. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ SABC3 “tests” Afrikaans programming, Screen Africa, April 15, 2009

Bibliography

- Adegbija, Efurosibina E. (1994), Language Attitudes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Sociolinguistic Overview, Multilingual Matters, http://books.google.be/books?id=Ghqf-m6ILIgC, retrieved 2008-11-10

- Alant, Jaco (2004) (in French), Parlons Afrikaans, Éditions L'Harmattan, http://books.google.ca/books?id=NKjBVF8krYIC, retrieved 2010-06-03

- Baker, Colin; Prys Jones, Sylvia (1997), Encyclopedia of bilingualism and bilingual education, Multilingual Matters Ltd., http://books.google.ca/books?id=YgtSqB9oqDIC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Berdichevsky, Norman (2004), Nations, language, and citizenship, Norman Berdichevsky, http://books.google.ca/books?id=_q14xoaXj1UC, retrieved 2010-05-31

- Batibo, Herman (2005), "Language decline and death in Africa: causes, consequences, and challenges", Oxford Linguistics (Multilingual Matters Ltd), http://books.google.ca/books?id=yoZ_fU_B0KgC, retrieved 2010-05-24

- Booij, Geert (1995), "The Phonology of Dutch.", Oxford Linguistics (Oxford University Press), http://books.google.ca/books?id=LT6E6YdAh-MC&dq, retrieved 2010-05-24

- Booij, Geert (2003), "Constructional idioms and periphrasis: the progressive construction in Dutch.", Paradigms and Periphrasis (University of Kentucky), http://cs.engr.uky.edu/~gstump/periphrasispapers/Progressive.pdf, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Brachin, Pierre; Vincent, Paul (1985), The Dutch Language: A Survey, Brill Archive, http://books.google.com/books?id=GeUUAAAAIAAJ, retrieved 2008-11-03

- Bromber, Katrin; Smieja, Birgit (2004), "Globalisation and African languages: risks and benefits", Trends in Linguistics (Walter de Gruyter), http://books.google.ca/books?id=lxjtToDh_g4C, retrieved 2010-05-28

- Brook Napier, Diane (2007), Languages, language learning, and nationalism in South Africa, in Schuster, Katherine; Witkosky, David, "Language of the land: policy, politics, identity", Studies in the history of eduction (Information Age Publishing), http://books.google.ca/books?id=AYfRwLd8LCEC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Conradie, C. Jac (2005), "The final stages of deflection - The case of Afrikaans "het"", Historical Linguistics 2005 (John Benjamins Publishing Company), http://books.google.ca/books?id=3fSsa7DPlNQC, retrieved 2010-05-29

- Deumert, Ana (2002), "Standardization and social networks - The emergence and diffusion of standard Afrikaans", Standardization - Studies from the Germanic languages (John Benjamins Publishing Company), http://books.google.ca/books?id=LYNHubXRzJAC, retrieved 2010-05-29

- Deumert, Ana; Vandenbussche, Wim (2003), "Germanic standardizations: past to present", Trends in Linguistics (John Benjamins Publishing Company), http://books.google.ca/books?id=o-qM3Wk4nZ0C&pg=PA15, retrieved 2010-05-28

- Deumert, Ana (2004), Language Standardization and Language Change: The Dynamics of Cape Dutch, John Benjamins Publishing Company, http://books.google.be/books?id=8ciimg5gGqQC, retrieved 2008-11-10

- de Swaan, Abram (2001), Words of the world: the global language system, A. de Swaan, http://books.google.ca/books?id=d-Jd5KkyFpwC, retrieved 2010-06-03

- Domínguez, Francesc; López, Núria (1995), Sociolinguistic and language planning organizations, John Benjamins Publishing Company, http://books.google.ca/books?id=aSlp7wze6OMC, retrieved 2010-05-28

- Donaldson, Bruce C. (1993), A grammar of Afrikaans, Walter de Gruyter, http://books.google.ca/books?id=ftzioRvJzTUC, retrieved 2010-05-28

- Egil Breivik, Leiv; Håkon Jahr, Ernst (1987), Language change: contributions to the study of its causes, Walter de Gruyter, http://books.google.ca/books?id=z7zlUp5Xuc8C, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Geerts, G.; Clyne, Michael G. (1992), Pluricentric languages: differing norms in different nations, Walter de Gruyter, http://books.google.ca/books?id=wawGFWNuHiwC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Gooskens, Charlotte (2007), "The Contribution of Linguistic Factors to the Intelligibility of Closely Related Languages", Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, Volume 28, Issue 6 November 2007 (University of Groningen): pp. 445–467, http://www.let.rug.nl/gooskens/pdf/publ_JMMD_2007.pdf, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Heeringa, Wilbert; de Wet, Febe (2007), The origin of Afrikaans pronunciation: a comparison to west Germanic languages and Dutch dialects, University of Groningen, pp. 445–467, http://www.let.rug.nl/~heeringa/dialectology/papers/prasa08.pdf, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Herriman, Michael L.; Burnaby, Barbara (1996), Language policies in English-dominant countries: six case studies, Multilingual Matters Ltd., http://books.google.ca/books?id=PpPNMf5ESsoC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Hiskens, Frans; Auer, Peter; Kerswill, Paul (2005), The study of dialect convergence and divergence: conceptual and methodological considerations., Lancaster University, http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fss/linguistics/staff/kerswill/pkpubs/HinskensAuerKerswill2005Conv.pdf, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Holm, John A. (1989), Pidgins and Creoles: References survey, Cambridge University Press, http://books.google.ca/books?id=PcD7p9y3EIcC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Jansen, Carel; Schreuder, Robert; Neijt, Anneke (2007), "The influence of spelling conventions on perceived plurality in compounds. A comparison of Afrikaans and Dutch.", Written Language & Literacy 10:2 (Radboud University Nijmegen), http://dare.ubn.kun.nl/dspace/bitstream/2066/56692/1/56692_JS&N20070001.pdf, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Kamwangamalu, Nkonko M. (2004), "The language planning situation in South Africa", in Baldauf, Richard B.; Kaplan, Robert B., Language planning and policy in Africa, Multilingual Matters Ltd., http://books.google.ca/books?id=nVrsAmvjhNQC, retrieved 2010-05-31

- Langer, Nils; Davies, Winifred V. (2005), Linguistic purism in the Germanic languages, Walter de Gruyter, http://books.google.ca/books?id=M9uNEf_FPVoC, retrieved 2010-05-28

- Machan, Tim William (2009), Language anxiety: conflict and change in the history of English, Oxford University Press, http://books.google.ca/books?id=XFKYdKGSEiAC, retrieved 2010-06-03

- McLean, Daryl; McCormick, Kay (1996), "English in South Africa 1940-1996", in Fishman, Joshua A.; Conrad, Andrew W.; Rubal-Lopez, Alma, Post-imperial English: status change in former British and American colonies, 1940-1990, Walter de Gruyter, http://books.google.ca/books?id=SIu244rlVu8C, retrieved 2010-05-31

- Mennen, Ineke; Levelt, Clara; Gerrits, Ellen (2006), "Acquisition of Dutch phonology: an overview.", Speech Science Research Centre Working Paper WP10 (Queen Margaret University College), http://eresearch.qmu.ac.uk/152/1/wp-10.pdf, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Mesthrie, Rajend (1995), Language and Social History: Studies in South African Sociolinguistics, New Africa Books, http://books.google.com/books?id=aIivedw-oZYC, retrieved 2008-08-23

- Mesthrie, Rajend (2002), Language in South Africa, Cambridge University Press, http://books.google.ca/books?id=cqaGb_SEQHUC, retrieved 2010-05-18

- Myers-Scotton, Carol (2006), Multiple voices: an introduction to bilingualism, Blackwell Publishing, http://books.google.ca/books?id=HdHMKJaw2Q0C, retrieved 2010-05-31

- Niesler, Thomas; Louw, Philippa; Roux, Justus (2005), "Phonetic analysis of Afrikaans, English, Xhosa and Zulu using South African speech databases", Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 23 (4): 459–474, http://academic.sun.ac.za/su_clast/documents/SALALS2005.pdf

- Palmer, Vernon Valentine (2001), Mixed jurisdictions worldwide: the third legal family, Vernon V. Palmer, http://books.google.ca/books?id=G9dys7IenowC, retrieved 2010-06-03

- Page, Melvin Eugene; Sonnenburg, Penny M. (2003), Colonialism: an international, social, cultural, and political encyclopedia, Melvin E. Page, http://books.google.ca/books?id=qFTHBoRvQbsC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Proost, Kristel (2006), Spuren der Kreolisierung im Lexikon des Afrikaans, in Proost, Kristel; Winkler, Edeltraud, "Von Intentionalität zur Bedeutung konventionalisierter Zeichen" (in German), Studien zur Deutschen Sprache (Gunter Narr Verlag), http://books.google.ca/books?id=ntrXXGDGoK8C, retrieved 2010-06-03

- Réguer, Laurent Philippe (2004) (in French), Si loin, si proche...: Une langue européenne à découvrir : le néerlandais, Sorbonne Nouvelle, http://books.google.ca/books?id=DAm0uHJGemQC, retrieved 2010-06-03

- Sebba, Mark (1997), Contact languages: pidgins and creoles, Palgrave Macmillan, http://books.google.ca/books?id=bRT_jZl39AMC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Sebba, Mark (2007), Spelling and society: the culture and politics of orthography around the world, Cambridge University Press, http://books.google.ca/books?id=JHgsfADZF9IC, retrieved 2010-05-19

- Simpson, Andrew (2008), Language and national identity in Africa, Oxford University Press, http://books.google.ca/books?id=I7qsTVO4IK4C, retrieved 2010-05-31

- Stell, Gerard (2008-11), Mapping linguistic communication across colour divides: Black Afrikaans in Central South Africa, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, http://www.researchportal.be/en/project/mapping-linguistic-communication-across-colour-divides-black-afrikaans-in-central-south-africa-%28VUB_500000000019265%29/, retrieved 2010-06-02

- Webb, Victor N. (2002), "Language in South Africa: the role of language in national transformation, reconstruction and development", Impact Studies in Language and Society (John Benjamins Publishing Company), http://books.google.ca/books?id=ujANkZqRALsC

- Webb, Victor N. (2003), "Language policy development in South Africa", Centre for Research in the Politics of Language (University of Pretoria), http://www.up.ac.za/academic/libarts/crpl/language-dev-in-SA.pdf

- Namibian Population Census (2001), Languages Spoken in Namibia, Government of Namibia, http://www.grnnet.gov.na/aboutnam.html, retrieved 2010-05-28

- CIA (2010), The World Factbook (CIA) — Namibia, Central Intelligence Agency, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/wa.html#People, retrieved 2010-05-28

Further reading

- Roberge, P. T. (2002), "Afrikaans – considering origins", Language in South Africa, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 052153383X.

External links

- The Ethnologue: Afrikaans

- Wordgumbo: Afrikaans

- An introduction to Afrikaans

- The New South African - Afrikaans - More about South Africa's official languages.

- Learn Afrikaans Online

- Afrikaans pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, culture

- Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge (FAK) - Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Associations

- Afrikaanse Taal- en Kultuurvereniging (ATKV) - Afrikaans Language and Cultural Association

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||